Using S3 for long-term photo backups

I’ve used various ‘free’ cloud storage solutions including Dropbox, Amazon Photos and Google Photos and when I hit the paywall have moved my photos to the next service that is feeling generous with their ‘free unlimited storage’ options. I

My situation at the start of this

- My home photo and video collection is roughly 100GB over 10 years and 4500 files - but I only knew this after getting it organised!

- A Dropbox of 19GB. Not enough storage for everything, but my goto for auto-upload from my phone (plus DropSync) and day-to-day storage

- Amazon Photos - I started using this as we have prime in my household and they offered free unlimited photo storage - but only 5GB for videos…

- Google Photos - Up next? Google Photos, free photos AND videos. Yes please! Then shortly after moving here they announced this free ride ends in June 2021 - after which you bank what you have and have 15GB additional. If you read this before June 2021, it might be worth dumping into it just incase!

After Google photos wanted paying, and partly after realising the truth of a quote I heard from Social Dilema “If you’re not paying for the product, then you are the product,” - I came to the conclusion I should pay a small amount of money, and have the solution I wanted.

Working in tech - I also work with Amazon, S3 and Terraform, so I thought I could achieve these aims, have fun and learn something.

Note: S3 is NOT a tool for managing your photo collection

To be clear I wanted somewhere to stick my photos (and maybe other backups) unaltered, at minimal cost, so that I’ll never lose access to them and could mostly forget about them. However S3 is not user friendly for working with photos in terms of cataloging, editing, tagging etc.

Therefore I’ll probably need a tool like Google Photos for reviewing them, but I do not intend to curate my photos, add metadata and save this back to S3.

If you wanted to use S3 and had the above intentions then you need to carefully think about the storage class implications and the related cost.

The Solution

The solution I settled on was an Amazon S3 bucket and S3 Glacier Deep Archive, and largely influenced from this article. He talks you through the UI process, but I decided to use Terraform which supports defining ‘Infrastructure As Code’.

Building

I did this on my Windows Surface, but for development activities like Terraform I prefer to work through WSL2 (Windows Subsytem for Linux)

Pre-requisites required are below, but can be setup quickly if needed:

- Create an AWS account

- Install the AWS CLI tool

- Download and install Terraform

- WSL2/linux if you want to use jhead (file renaming tool, mentioned later)

Terraform content

I used Terraform to create the following resources:

- S3 bucket to contain the files

- Lifecycle policy to move files to Deep Glacier (after 10 days)

- IAM user to populate it (which I created for using with ODrive)

- Permissions for that user on S3

- API key to be grant access from ODrive

The full terraform file can be seen here

Migration plan

OK but how to get all the photos from my ..mess.. into S3? I decided to use another tool I’ve used for a while. ODrive.

ODrive is a great tool for working across cloud storage providers using your operating systems file system. So for me this was the Windows Explorer and some basic commandline.

Note: ODrive too has moved further away from being free - and for this reason it may not be great for you. I made use of the Unsync feature which is great if you don’t have a large hard drive and only want to have part of your hoard on disk at any one time - but it requires a premium trial or a paid for account.

Organising the content

Everyone has their own system, and your content may be different. With the age of AI and image recognition, I generally favour unstructed data/storage (bucket) and tools like Google Photos and those of the future that can always infer structure later. As well as the data derivable from the image itself such as people, seasons, and occassions, images also have quite good Exif metadata attributes including potential for ‘Date Taken’, ‘Device’ and ‘GPS location’.

In practical terms looking at a folder on windows can be a pain if they’re too massive, so I found the best balance was to loosely have a folder structure as <Year>\[Source\]

One reason I like dropbox is it names the files in a yyyy-mm-dd hh.mm.ss[-n].jpg which makes them relatively descriptive and searchable by filename. Also as S3 supports prefix based search this benefit can exist there too.

A great tool I found for ‘fixing’ any filenames that didn’t meet this convention was jhead. This tool supports renaming files based on image Exif metadata or where that is missing, using filesystem datetimes. The command I used for this is:

jhead -n"%Y-%m-%d %H.%M.%S" ./input

This renames to the convenient ‘descending’ datetime pattern and also adds a counter (only when required) for images from the same datetime.

Migration

As I mentioned before, to do this I used ODrive and their S3 adapter, which still lets you interact with this as a normal filesystem.

I curated the files on Amazon Photos, as Google Photos lacks good ODrive support, and once the files were organised by year and anything not worth keeping had been deleted, I copied them across into the ODrive S3 structure. If you have Google Photos and a large enough hard drive, you could use their Google Takeout service instead.

After this, I let ODrive do its thing and sync. Note this does take time. There’s plenty of more time-efficient methods I’m sure e.g. zipping them up. I just left it running overnight, and I wanted them to be stored relatively raw and make future updates simple so decided against compression (as S3 storage is cheap).

Verification

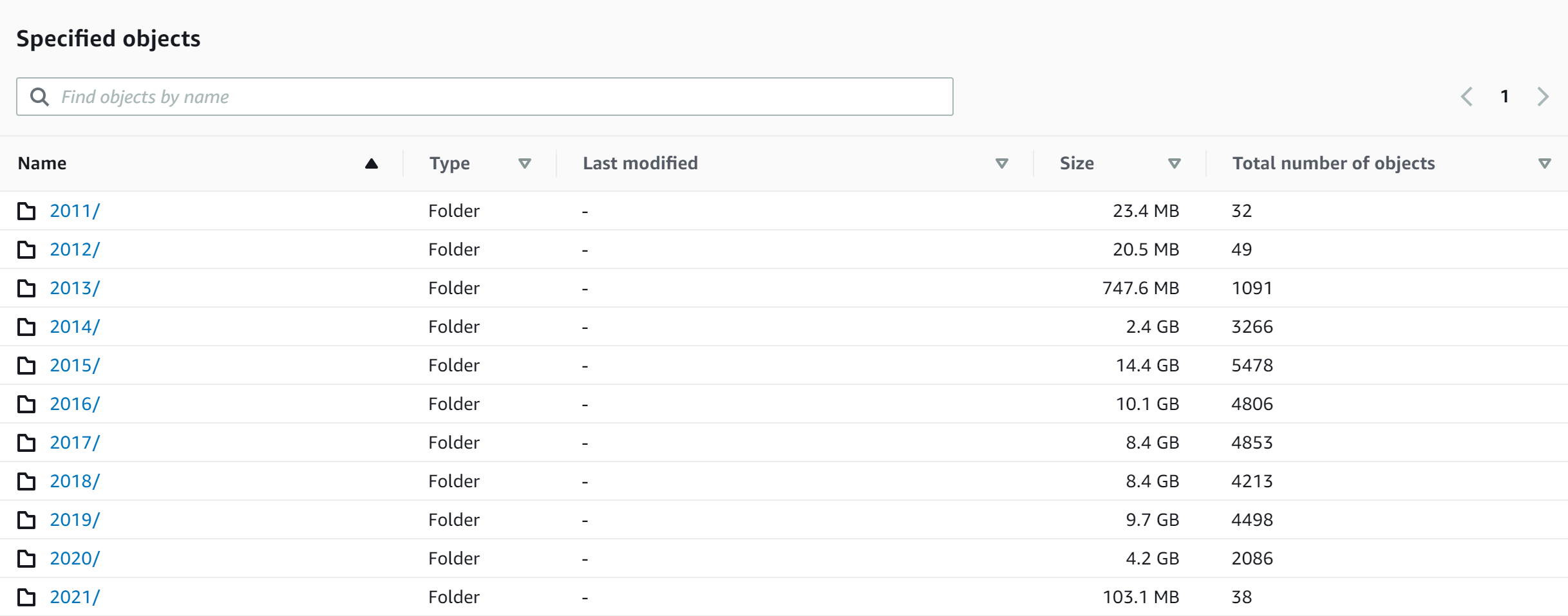

If you’re like me, and these are your family memories, you’ll want to make sure you’re doing this correctly! The easiest way I found was to

- Get the folder’s properties for ‘YYYY’ on Windows, and then

- On S3 select that folder, click Actions->’Calculate total size’

- Compare folder properties and S3 to ensure the file count and folder sizes match

Conclusion

Lets be honest - if you do have a preferred cloud provider, you can probably store your content with them for less effort and only a bit more cash. You will also likely get some more photo management features. This is what most folk will do! This isn’t going to make a big change to your budget.

However, if you’re like me, you want to have better control of your data, are interested in DIY-tech or want something cheaper for the long haul without having to keep switching to the next best ‘free ride’ - then this can work great.

I’m now also facing a Jevons Paradox that now I have unlimited and cheap storage, I’m wondering what else I can store!

UPDATE 28/03/2021

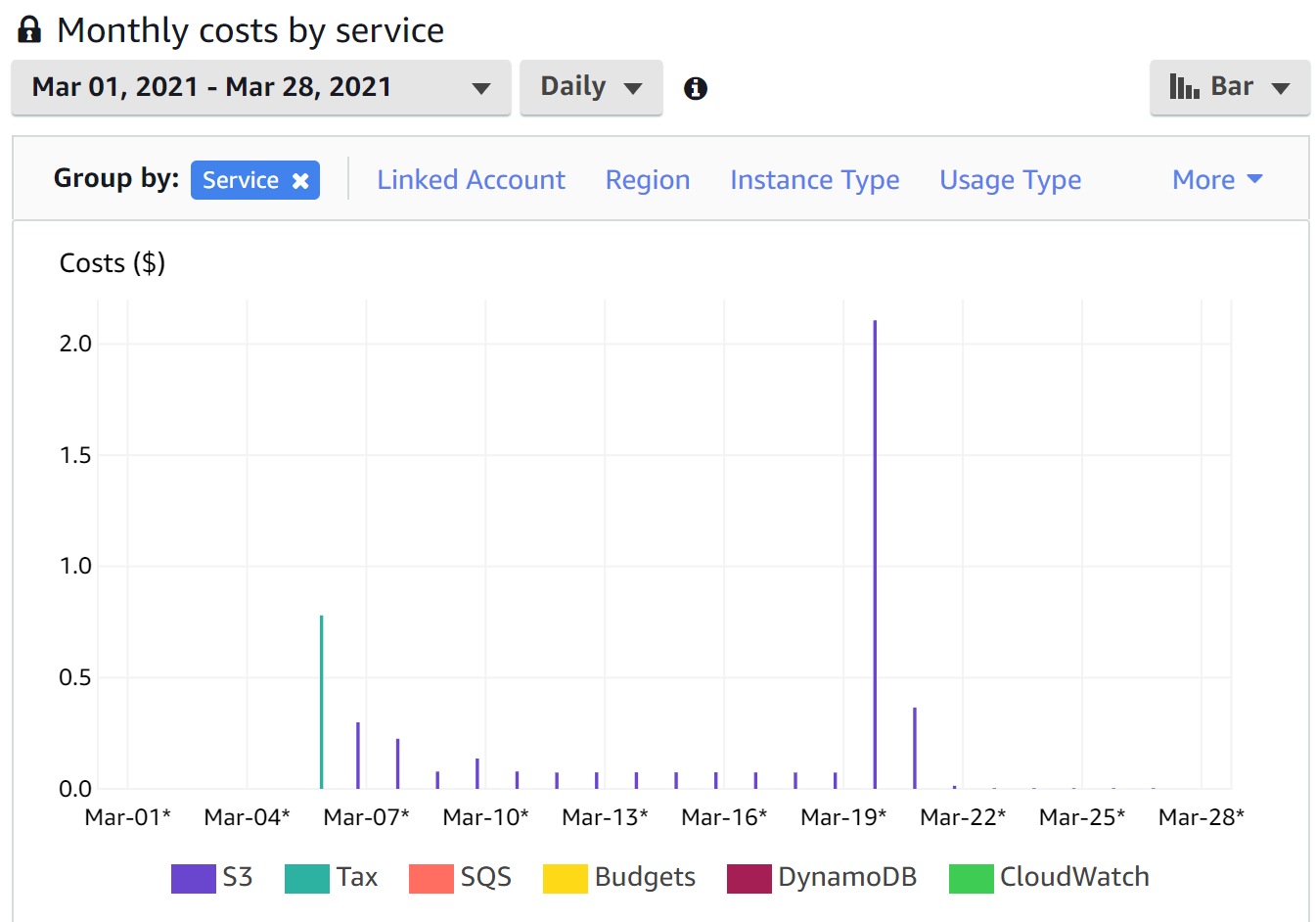

Confession - I didn’t get this right first time, and also I hadn’t originally understood the impact of the S3 transition costs.

So there are a number of S3 costs, but the ones that are key here are effectively charges for writes, reads and storage class transitions. Also worth stating that regions are not priced equally.

The below image shows my costs, with S3 remaining in standard storage longer than I intended (at approx $0.07 per day), and then after fixing this you can see a spike of $2.11 when these transitioned from standard to deep glacier. I’ve now been running at $0.00 per day according to cost explorer, which I’m sure will round up every few days to $0.01. There’s also $0.78 for tax. So after fixing it, it’s now looking good!

I’m a big fan of fast and frequent feedback, so if you want to let me know what you think you can get in touch on twitter until I setup comments.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *